By Jeremy Corbyn

On February 15, 2003, well over a million people marched through London to oppose the intended invasion of Iraq.

It was the biggest ever demonstration in British history. Six hundred other demonstrations took place all aroundthe world, on every continent.

They all knew why they were marching and, by sheer force of numbers, turned media and popular opinion around from the Government’s intended story that somehow Iraq presented a threat to us all and that only by bombing could we secure the peace of the region and,indeed, the world.

More than a decade later, billions spent, hundreds of thousands dead and more wars than ever, the sheer futility of war and its waste is there for all to see.

The victims lie dead in unmarked graves amid the rubble, or the soldiers from the West are in heroes’ graves, in well-tended cemeteries, but still dead in their youth.

As Europe goes through a strange paroxysm of mawkish memorial of the Great War and a nasty dose of xenophobic, inward-looking behaviour, we need to learn from history of those who tried to stop that war and tried to point out where it could lead.

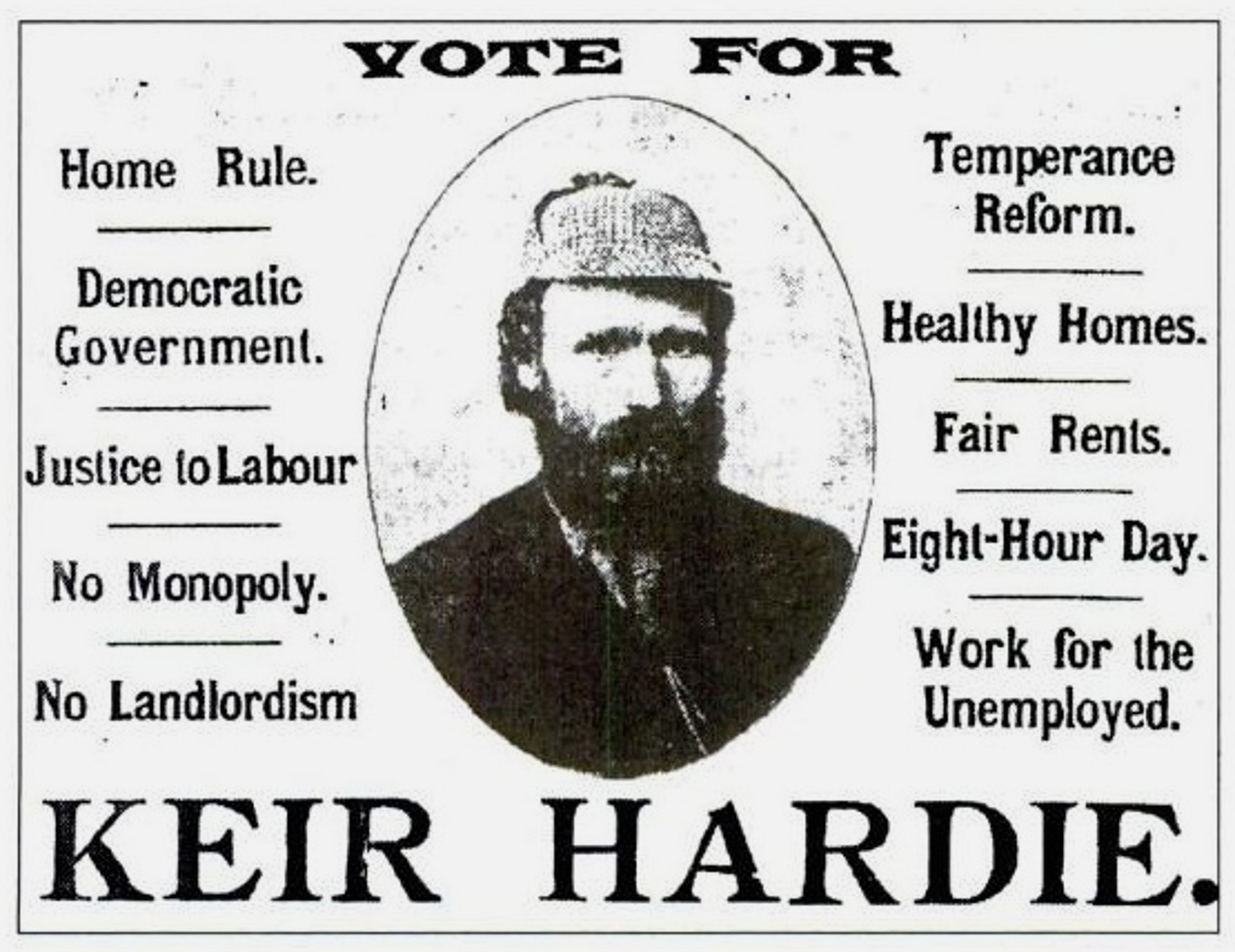

Keir Hardie’s life, impressive by any standards, had a universal and global vision that was verydifferent from many other great labour figures of the pre-1914 period.

It seems astonishing,at this distance, that on August 2, 1914, two days before war was declared, he spoke in Trafalgar Square at a rally where a declaration was adopted, which concluded bystating: “Men and women of Britain, you now have an unexampled opportunity of showing your power, rendering magnificent service tohumanity and to the world. Proclaimfor you that the days of plunder andbutchery have gone by. Send messagesof peace and fraternity to your fellows who have less liberty than you.

“Down with class rule. Down withthe rule of brute force. Down with thewar, up with the peaceful rule of thepeople.”

Eighty-nine years later, Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair told Parliament that there was no alternative to going to war with Iraq, even after he and Foreign Secretary Jack Straw had failed to gain a second UN resolution specifically authorising war.

The legacy of Hardie, and indeed the contradictions in the Labour Party between the ideal of national war asthe supreme form of patriotism andthe wider global tradition of peace and fraternity, is still there and self-evidently not resolved.

Hardie had an amazing global view. For someone who was born with no privileges of any kind, no opportunity to travel and very limited education, he had a thirst for learning and a deep appreciation of the unity of peoples in different circumstances all across the globe.

Hardie’s own world view came through the prism of a vast British empire which nurtured British children in the belief that somehow they benefited from the empire and were superior to the rest of the world.

The inherent racism in that message was powerful and remains so. In his early days as a trade union representative, he opposed Irish immigration into Scotland. Later, however, he went on to oppose segregation in South Africa during his visit there and went well beyond anyother opponents of the Boer War insupporting the African and Asianpeoples of South Africa.

In India, he was threatened with deportation for supporting home rule and consorting with the newly formed Congress Party.

But it was his attempts to build an international peace organisation that was his most groundbreaking work. The late 19th century saw the founding of the First Working Men’s International and, almost in parallel, the attempts by the Tsar of Russia and others to found an international treaty through the Hague Convention.

Hardie worked hard to unite all peace groups as though he knew the dreadful day would arrive when Britain, France, Germany, Russia and the Ottoman empire would all be at war with millions ofworking men lined up against each other.

As war fever intensified, Hardie stepped up his efforts and in 1913, only eight months before war was declared, hepresided over an enormous peace rallyin the Royal Albert Hall.

Hardie died two years later, essentially a broken man. All he had striven for in the sense of international working-class unity against the industrial killing machines of the Great War had been overridden by the jingoistic, crude propaganda of the Allies.

A century later, the general mood is more sanguine about World War I. A war between nations, all led by cousins and nephews and a son of Queen Victoria, it was at once a war led by a massively dysfunctional family and the huge commercial interests that were involved.

The above is an extract from a new book "What Would Keir Hardie Say?" edited by Pauline Bryan, which can be purchased here.