Choose to fight!

By Mike Cowley and Vince Mills

Foreword

John McDonnell MP

There have been many times in the history of the Labour Party when the political positioning of the leadership has called into question whether it is a vehicle socialists can have any faith in to advance their cause.

The passage of Keir Starmer from ardent advocate in the 2020 leadership election of the radical policy programme he inherited from Jeremy Corbyn and myself to the austerity implementing prime minister of recent times, has made many despair of Labour as a force for progressive change let alone socialism.

The centralising control of the party structures preventing debate in constituency parties and the control of candidate selection at every level of representation has resulted in many active party members giving up hope of restoring any democratic control back into the hands of party members.

So, is it time to give up on Labour and look to something else?

It’s a valid question but it requires a hardheaded response based upon the harsh realities of our electoral system, the history of the working class in our country and the numerous attempts to create a viable alternative to Labour.

The First Past the Post system for UK wide elections means it has proved so far impossible for a third party from the Left to challenge for government the two major parties successfully at the UK national level.

Every attempt so far to launch a Left party from outside the Labour Party has failed to gain lift off and has often degenerated into sectarian infighting.

The rise of Reform is cited as an example of how a third party can be created and scaled up to threaten both traditional parties.

The reality is that Reform has been allowed to emerge and grow because the establishment needs an alternative to the imploding Conservative Party.

Reform is capital’s fallback if the Conservatives collapse after successive failed leaders and corrupt incompetent administrations.

No party of the Left will be given the free ride that Reform has so far by the establishment and its media.

The full force of the establishment would be thrown against it.

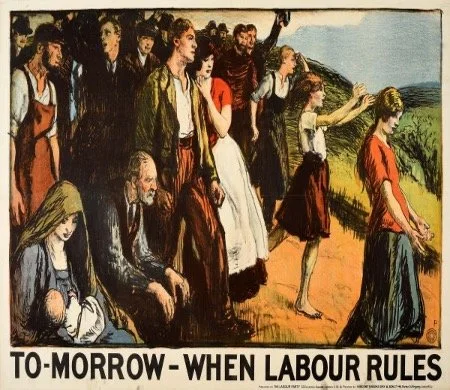

The founders of the Labour Party knew the scale of the challenge they would face and were only able to withstand that threat by establishing the party on the robust foundations of the century old trade union movement and on welding together the broadest progressive political alliance possible.

At different stages in its history different tendencies within that broad church have had a majority influence in the party. The party has been a terrain of struggle over what strain of politics would dominate at any time. This has been influenced often by campaigns and movements in the wider society.

Currently a new wave of protest and trade union and political action is building in our communities. Inevitably that struggle will permeate and force change onto the agenda of the Labour Party.

That’s why now is not the time for socialists to give up the ground and lose the emerging opportunity of rebuilding Labour as a force for the socialist and progressive transformation of our society.

In Scotland, the Scottish Labour Campaign for Socialism continues to organise in the spirit of the Party's founder, Keir Hardie. This pamphlet serves as a reminder of the tasks ahead, and why you should join them.

Introduction

‘What are you doing in the Labour Party?’ So asked Vince Mills, author of the original pamphlet, updated here for a very different political landscape more than two decades after it was first published. There is, from some perspectives, no satisfactory reply to this question. The early months of Keir Starmer’s Labour government, elected on a wave of apathy and a strategy of minimising expectations, leaves Socialists open to accusations of collaborating with a party its detractors argue is nothing more than a Trojan horse for neo-liberal continuity.

On the contrary, we want to argue that even if there was no Left in the Labour Party, it would be necessary to create one. The role of Labour Party Socialists and our organisations is to create the space within which socialist ideas gain credibility and traction. In the longer term our orientation has the potential of winning over a party capable of delivering state power at Scottish and UK levels. More of this later. Firstly, we want to consider some of the arguments typically used to attack the idea that the Labour Party is an acceptable place for socialists to work within.

There are three interrelated positions. The first is that by its very nature the Labour Party is designed to hobble Socialist progress in particular, and the more radical ambitions of the labour movement more generally. On this reading, the Labour Party is not an organisation capable of reform. It has been since its founding a means of frustrating rather than facilitating working class power. Indeed, some sections of the Left argue that, created in the image of the labour aristocracy, the Party’s objective historical purpose was to defend and promote British imperialism in order to privilege the interests of a select number of skilled workers and their allies in the liberal middle classes. Such a case is put in R. Clough’s Labour; a Party Fit for Imperialism (2014), or more recently, Donny Gluckstein’s the Labour Party: A Marxist History (2019).

The second position is that the Labour Party had the potential for being radically transformed, especially during the 1980s. This is the argument advanced by Panitch and Keys in the End of Parliamentary Socialism (2001). It is a variant of a wider, more popular mythology of a golden age of radicalism in the Party exemplified by the 1945 Attlee government.

Here, the argument is essentially that Labour was once capable of significant reform but has now been captured by what Hutton calls ‘feral capitalism.’ It cannot now be saved and Socialists should look elsewhere. Closely aligned with this argument is that Labour, born out of an alliance with the working classes and their trades unions, ceases to be a party of that class when these links are loosened or broken altogether. Tensions between the Parliamentary Labour Party and the unions were addressed in Vince Mills’ original pamphlet. Those strains have hardly disappeared, and in Unite leader Sharon Graham’s exhortation of the government to implement a wealth tax on the 1%, and in her claim that the New Deal for Workers is ‘unrecognisable’ from its early drafts, we see those stressors emerge in a different and perhaps more volatile political environment. Again, critics of Labour Party socialists see in these pressures a portent of the last days of Labour as we have understood it. Socialists should therefore look elsewhere for salvation.

This takes us neatly to the third strand in the arguments for exiting the Party. When the original pamphlet was published, the Scottish Socialist Party and the Socialist Alliance in England offered attractive alternative vehicles for electoral challenge. Now, extra parliamentary movements around Palestine, climate change and against austerity are cited as offering the Left an opportunity to reorient towards street campaigns light years away from Starmer’s closeted parliamentarianism. Jeremy Corbyn and Zarah Sultana’s Your Party, as well as Zack Polanski’s eco-populist Greens, provide more contemporary party-based alternatives. However, the questions asked 20 years ago remain on the table, albeit posed to different political actors working in changed circumstances; what are the politics of these movements and parties? How can they cohere around a shared socialist programme that aligns with working class concerns? On what basis can disconnected, often single-issue campaigns (or parties disconnected from trade union organisation) achieve the transformation from capitalism to a socialist society? Indeed, unlike previous efforts to build parties outside of Labour, single issue campaigns frequently do not have a broader aim beyond their immediate demands. More often, effective street campaigners such as Living Rent are wary of broader political programmes distracting from their single-minded focus on housing, public services, racism or the climate. In their eagerness to escape the deadening clutches of a Labour Party now apparently wholly in the hands of technocratic political class hostile to political agency outside of Westminster, some on the Left have ignored these questions altogether. This is understandable, but not justified.

The Case Against Membership of the Labour Party

The case made in Labour: A Party Fit for Imperialism (2020) is a serious one. The book catalogues the history of imperialist abuse that took place under successive Labour governments. Some of these will be considered later. While there may be disagreement as to how Socialists might have responded to specific situations (the 1916 Nationalist uprising in Ireland is a case in point), there is no doubt that over the history of the 20th and now 21st centuries Labour was a staunch defender first of British and later of US imperialism.

Indeed, ex Leader Jeremy Corbyn is on record as describing his internationalist politics as key to the establishment campaign to discredit and defame him from 2015 onwards. The Party’s record since 2019 – on everything from arms sales to Saudi Arabia, Black Lives Matter, the emulating of Tory anti-immigrant and Islamophobic rhetoric and unwillingness to support the struggles of the Palestinian people for peace and self-determination - demonstrate that the ‘new management’ remains firmly affiliated to colonial assumptions.

The book identifies the source of this approach in the origins of the Party. Clough argues that Labour was founded in the explicit interests of the labour aristocracy. Explaining the introduction of the Party’s 1918 constitution which ended the practice of members joining through constituent bodies like the Fabian Society, the ILP or individual unions, the authors argue that:

‘The Russian Revolution had a further consequence; it forced the ruling class to concede universal suffrage to men over 21 and women over 30…this would more than double the electorate. Labour’s social base amongst the more affluent sections of the working class, and in certain layers of the middle class, would in itself be far too narrow an electoral base to enable it to become a significant parliamentary force in the post-war world. To continue to defend their interests, it would have to broaden its electoral support, and the only constituency it could appeal to was the newly established enfranchised section of the working class. Labour had to establish proper local Party organisations which could serve to mobilise that vote; to prevent any challenge to the domination of the ‘Labour aristocracy’ it had to keep such organisations under tight control.’

Keir Starmer’s authoritarian slash and burn approach to Party democracy would certainly seem to fit this analysis.

However, the flaws here are fairly self-evident, although it is certainly the case that the 1918 constitution, including the adoption of Clause 4, was designed to marginalise Socialism in the Labour Party while keeping Socialists active in its ranks.

Firstly, the argument suffers from organisational determinism. ‘Once an imperialist party, always an imperialist party.’ This position is all the less credible since the broader electorate empowered by the increased franchise may not necessarily have had shared interests with the ‘Labour aristocracy,’ a concept which is itself open to challenge.

Further, the Socialist groupings and individuals active in the Labour Party did challenge Labour’s quiescence. The ILP in particular in Scotland continued to be the local active face of Labour on the ground. Throughout the 1920s, according to the ILP on the Clydeside (1991), far from simply complying with the Party’s rightward drift:

‘The leading members (of the ILP) came to believe that ‘socialism’ could be achieved more rapidly than most Labour Party leaders thought possible and that in the process many more of the rules of liberal capitalism could be broken, notably free trade and balanced budgets.’

In fact, an organised presence persisted in the Labour Party even after the ILP’s disaffiliation in 1932. Until that point the ILP functioned as a more or less organised opposition. Since then, the left has, at times, made a serious challenge for the Leadership of the Party, none more so than in 2015. Before that, the left challenge of the 1970s and 1980s is the subject of Panitch and Ley’s book. However, their conclusion is hardly more optimistic than that of Ralph Miliband, writing in his conclusion to Parliamentary Socialism (1964) on the politics of the Party:

‘What this means is that the Labour Party will not be transformed into a party seriously concerned with socialist change. Its leaders may have to respond with radical sounding noises to the pressures and demands of its activists. Even so, they will see to it that the Labour Party remains, in practice, what it has always been – a party of modest social reform in a capitalist system within whose confines it is ever more firmly and by now irrevocably rooted. That system badly needs such a party, since it plays a major role in the management of discontent and helps to keep it within safe bounds; and the fact that the Labour Party proclaims itself at least once every five years but much more often to be committed not merely to amelioration of capitalist society but to its wholesale transformation, to a just social order, to a classless society, to a new Britain, and whatever not, does not make it less but more useful in the preservation of the existing social order.’

Would Miliband, writing as a decade of social upheavals across class, race, gender and sexuality swept Western societies, and in the midst of anti-colonial uprisings in Algeria and elsewhere, have modified his view in light of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership victory in 2015? Corbyn met and spoke with Miliband on numerous occasions. He will not have been unaware of Miliband’s scepticism towards the socialist project inside the Labour Party. Certainly, Miliband’s locating of the Party as a political tributary diverting social discontent into reformist impasse is borne out in the ferocity of the campaign orchestrated by the establishment inside and outside the Party, in particular in the wake of the 2017 General Election result. The ruling class looked poised for one tantalising moment to be in danger of losing control of Labour.

Despite this, Corbyn’s victory, and the hope it briefly catalysed for millions, remains a warning to power that Labour can, in specific conditions, become a vehicle for a politics of change, a light at the head of the kind of mass mobilisation of public opinion the ruling class fear.

It is obvious from Miliband’s quote that the Labour Party of the sixties was much more left-wing in its rhetoric than the unapologetic, neo-liberal apostles of today’s leadership. In fact, Starmer’s ‘changed Labour Party’ positions itself as openly hostile to socialist ideas in general. The Labour Together organisation appears operated by people singularly focused on office as a goal in and of itself. Political ambition is scorned, while the raising of ‘unrealistic’ hopes is dismissed as nostalgia for a politics whose time is gone. These are the ‘Clause 1 socialists,’ a self-selecting clique for whom independent actors outside the corridors of political power are a peripheral mass to be roused only as far as the ballot box every few years.

However, as Miliband makes clear, the rhetoric of the period he cites was always limited to words. It therefore remains a surprise when some ex-Labour Party members justify leaving the Party by arguing that its latest shift rightwards is irrevocable and unprecedented, as opposed to a mythical time when things in the garden were not just rosy but positively red. The history of the Labour Leadership, in and out of power, paints quite another picture, and in less attractive colours.

And if You Know Your History

As RH Tawney observed, “In 1918 the Labour Party finally declared itself to be a socialist party. It supposed and supposes, that it thereby became one. It is mistaken. It recorded a wish, that is all; the wish has not been fulfilled.”

The Labour Party is and has been since its inception an alliance of forces, the most powerful of which have always accepted the capitalist system, a position consistently sanctioned (and as a consequence extended a measure of political authority) by the block votes of the trades unions. Labour has been shaped since its inception by a reformist ideology founded on a tacit compromise: the economic, social and most importantly political demands of Labour and the working class are confined to what is acceptable within the system and achievable within the rules of that system as long as the state continues to provide improved living standards and a welfare cushion for the working class. As Pelling remarks in his classic study of the Party’s origins:

“…the Labour Representation Committee represented an alliance of forces in which the socialists, organised as such were only a tiny fraction…The Labour Party was in fact not committed to socialism as a political creed to 1918; and both before and after that date especially in the early years it contained many who were hostile to it…there is little doubt that most of the non-socialist trade union leaders would have been happy to stay in the Liberal Party…if the Liberals had made arrangements for a larger representation of the working class among their parliamentary candidates.”

The resistance of many TU leaders to severing their relationship with the Liberals, and therefore to the building of an explicitly class-based party, runs contrary to the arguments traditionally tabled by the extra-Labour Party left. Namely, that those same leaders were decisive in establishing the party as a bulwark against independent working-class agency. In fact, it was Hardie’s experience of working with a Liberal Party he came to understand would always side with the ruling class in matters of class conflict that drove him towards the founding of an independent party of labour. Much of the trade union bureaucracy had to be dragged kicking and screaming to the LRC.

Clause IV can be seen in this context as a sop to a left clearly marginalised by the 1918 constitution. It was not the 657 local activist branches of the ILP (itself a broad church) which were to be the basis of the Labour Party but local representation committees and trades councils. It became possible for the first time to become a direct member without being a member of an affiliated union or socialist society. This undermined the role of the ILP, which had at least attempted to provide a political education for its members. Further, the 5 socialist society places on the NEC were abolished in order to placate the unions, leaving local Party activists and ILP members alike without representation on the NEC for the next 19 years.

Precisely what kind of leadership had been created is vividly illustrated by the two short periods of government the Labour Party enjoyed before the second world war.

The Pre-War Governments

In 1924 a political earthquake erupted in British politics with the coming to power of the first, minority Labour government, or so you would have thought if you believed the ravings of the capitalist class. The Duke of Northumberland predicted the introduction of free love, a recurring trope in the fevered minds of our moral gatekeepers.

The reality was of course somewhat different. Ramsay MacDonald, who had claimed that parliamentary government would give Labour the same power as the revolution had given Lenin, was unwilling to use that power on behalf of working-class interests. Lloyd George said of the government: “Their tameness is shocking to me.”

The most radical of Labour’s proposals at the time – the capital levy – was quietly dropped. It was a period of severe industrial conflict which did not abate with Labour taking power, and the government made it clear that it would, if necessary, use the Emergency Powers Act to deal with strikers. It did little to address unemployment, despite campaigning in 1923 under the banner ‘Work or Maintenance.’ In office it looked to trade revival to resolve the crisis, an approach Rachel Reeves would broadly emulate a century later. The administration collapsed amidst a debacle over failing to prosecute JR Campbell, the editor of the Communist Workers Weekly, which had published an article calling on soldiers not to shoot fellow workers.

Despite a heavy defeat in the 1924 General Election and intense criticism from the Clydeside ILP MPs, MacDonald survived to exert a dominant hold over the Party throughout the 20s. In the 1929 General Election, Labour became the largest Party in the House, and although it did not achieve an overall majority it was able to form a government. It could hardly have come to power at a more challenging time for a reforming social democratic government.

The Wall Street crash of 1929 sent economic shockwaves crashing through the markets of the capitalist world. By January 1930, unemployment stood at over 1,500,000. By the end of the year, it was 2,750,000. There was a massive budget deficit and the Bank of England faced a run on the pound and a rapid depletion of gold as foreign creditors demanded their deposits from a bank unable to pay in currency due to an international moratorium.

It was a crisis that cried out for radical measures, but the Labour Party had rejected even the Keynesian ideas of the ILP’s ‘Socialism in our Time’ and had no alternatives to orthodox capitalist assumptions. The government asked for a loan from the American banker JP Morgan. It was agreed only on the condition of a package which included a 10% cut in unemployment benefits. The burden of the crisis was to be shouldered by the poor.

It split the Cabinet. Eleven were in favour of the cut, with nine against. MacDonald met the King to proffer the resignation of the Labour Government. On his return, he announced the creation of a National Government including the Liberals and Tories. In the 1931 General Election Labour lost two million votes and 235 seats. But perhaps the most surprising thing of all was that despite his expulsion, MacDonald was not universally reviled by the Labour Party.

Margaret Bondfield and Stafford Cripps were among prominent members of the Party who wrote to express admiration for MacDonald’s actions. According to observers at the time, MacDonald remained a persuasive presence in the Party, even after the debacle of the National Government. Commenting on the experience of the Labour government, a French Labour historian of the 1930s said, “I tell you frankly that I shudder at the thought of the Labour Party ever having a real majority, not for the sake of capitalism, but for the sake of socialism.”

The 1945 Labour Government

In 1945, the Party did indeed achieve a large majority. The administration is often looked on by the contemporary Left as a golden age for socialism in the Labour Party, a somewhat ironic perception given that it was an administration composed largely of Labour right-wingers. Certainly, Labour did bring about many changes in social provision. The NHS was founded in 1948, the Education Act was implemented, a national insurance scheme was introduced and anti-union legislation was repealed.

Nevertheless, despite popular mythology Labour was hardly more radical in its economic policies than the government of 1929. It is true that a considerable amount of nationalisation took place incorporating coal, electricity, gas, and much of inland transport. But this happened without serious opposition from capital which clearly did not see this approach as a challenge to its power. The nationalisation of the Bank of England was greeted by the Tory Spectator magazine with these words:

‘There is not the slightest ground for regarding the Bill as necessary, but not the slightest either for regarding it as a calamity.’

The muted nature of the capitalist response can be understood when we consider that the 1945 Labour government effectively abandoned the war time planning machinery which could have been used to lay the basis for a planned economy, undermined private control of the economy and built the foundations for socialist advance.

In short, and given the groundswell of support for a government described by Winston Churchill in the ‘Gestapo Speech’ as preparing the introduction of a ‘secret police,’ the ruling class no doubt saw such top-down nationalisation as significantly less troubling than they had anticipated.

Furthermore, reliance on the Marshall Plan firmly wedded Britain to US aid, the US economy and our full participation in NATO. Any sign of deviance from this line was suppressed. In 1948, thirty-seven Labour MPs sent a telegram of support to Signor Nenni, the left socialist candidate in alliance with the Italian Communists. The Labour Party executive extracted retractions or denials from 16 of the MPs and a pledge of renewed loyalty under threat of expulsion from the remainder.

The General Election of 1950 returned Labour with a majority of only six. The Korean War forced up the price of raw materials and coincided with major British expenditure on defence. Attlee, in some corners known as the ‘Father of Britain’s nuclear bomb,’ had committed millions to what he saw as a ‘nuclear deterrent’ without a debate in either parliament or the Labour Party. Partly to pay for this, Gaitskell introduced a deflationary budget which increased taxation and imposed charges on spectacles and false teeth. Bevan and Wilson resigned. British involvement in Greece, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaya and Vietnam point to a failure to fully relinquish the colonial assumptions of previous British administrations.

In October 1951 Attlee called a new General Election. Despite polling more votes than the Tories, Labour found itself in opposition, where it remained until 1964.

Out of Office

It might have been hoped that out of office the Labour Left would seize the initiative and develop a detailed plan for socialising the British economy. The disappointments of the Attlee period might have catalysed such a response. Precisely the reverse happened. It was the Right’s most creative period; the most coherent case for the revisionist approach came from Anthony Crossland and it had a wide range of support within the Party. Essentially, Crossland argued that capitalism had changed, that there was more diversity in the class structure than ever and an upward trend in incomes, developments that obliged the Labour Party to modernise and drop its insistence on nationalisation for its own sake. Bevan’s response, In Place of Fear (1952), argued that the basic class and power structures in Britain had not changed, and that the private sector had not given up the right to dispose of economic surplus as they, and not the state, thought fit. In the Future of Socialism (1956), Crossland restated his position that Britain was no longer capitalist in the traditional sense of the word. Indeed, ownership of the means of production was an increasingly irrelevant issue. The emphasis, he argued, should be on achieving equality through more effective redistributive means.

Following Labour’s third electoral defeat in 1959 the revisionists led by Hugh Gaitskell were anxious to dump Labour’s cloth cap image. Gaitskell argued for the replacement of Clause IV with generic declarations of socialist values implying support for the mixed economy. Gaitskell’s defeat probably resulted more from the hostility of the trade unions than any traditional attachment to socialist transformation across the Party. One target of the revisionists was the perceived industrial militancy of trade unions. The removal of Clause IV was therefore seen as a challenge to the independent bargaining powers of the trade unions, rather than an affiliation to collectivist principles.

Indeed, some union leaders could be equally hostile towards the left. Arthur Deacon of the TGWU demanded Bevan’s expulsion for indiscipline. It could be argued that it was just this sort of union opposition to Gaitskell which helped swing the vote for unilateral disarmament in 1960, and why that commitment melted away so quickly, so that a year later, it was defeated.

With Gaitskell’s death, Harold Wilson became Leader of the Labour Party in 1963. In 1964 Labour returned to power with a majority of five, a majority which grew to 100 following the 1966 election. Although considered to be on the left, Wilson’s support was largely drawn from the Gaitskellites, and he grew to treat the left with a barely concealed contempt.

Opposition to the Common Market was ignored when Britain re-applied for membership in 1967. Health charges were introduced, restrictions on immigration were tightened and perhaps worst of all official support was given to US offensives in Vietnam. The opposition to the Vietnam war radicalised a generation of students and Labour left activists. But it took place largely outside the Party.

Once again it was in conflict with the unions that the right-wing leadership of the party tasted defeat. In 1969, Barbara Castle, Minister of Employment and Productivity published In Place of Strife, proposing conciliation pauses, compulsory strike ballots and Ministerial settlement of inter union disputes. The right-wing leader of the AEU said that the penal clauses sounded ‘the death knell of British trade unionism.’

The Chief Whip made it clear to Wilson that they could not guarantee a majority for the Bill because many union-sponsored MPs would not support it. Under pressure, Wilson agreed a voluntary code with the trade unions – a Programme for Action – and the Bill was dropped.

The 1974 Victory

Despite expectations to the contrary, Labour lost office in 1970. When it returned in 1974 it was as a minority government in the midst of an oil crisis and the aftermath of the miner’s strike. When Labour went to the polls for a second time in October it managed to secure a fragile majority of three. Labour’s 1973 Programme for Britain formed the basis of its election manifesto, and showed an increased influence of the left, an influence partly attributed to a shift to the left in the trade unions. The Programme called for a ‘massive and irreversible shift in the distribution of wealth and income in favour of working people.’

This rhetoric did not however signal a substantive shift in direction. The government did dismantle Tory anti-union legislation but only to replace it with the voluntary controls of the Social Contract, and the instruments to bring about a more planned economy were never seriously contemplated.

Although the Party opposed entry to the Common Market, it was up against, amongst others, its own parliamentary leadership. Indeed, Labour in office was almost a mirror image of the 1920 government. In order to obtain an IMF loan, there were massive cuts in public expenditure. High unemployment followed, then a parliamentary pact with the Liberal Party and restrictions on wage levels. In 1978 under the Social Contract, Labour administered a real cut in the standard of living of 8%. As Eric Peston put it in Labour in Crisis (1983), “So as the economic crisis deepens the response of the Labour leadership becomes as predictable as any moderate Conservative response could be.” Wilson and Callaghan turned Tory crimes into ‘inescapable’ and ‘regrettable’ acts of ‘responsible statesmanship.’ The door was left ajar for Thatcherism.”

The Reaction to Thatcher’s Victory

Michael Foot was elected in 1980 as a stop gap leader, principally on the basis that he alone could hold the Party together. That in itself was no mean feat. Unlike the period of Labour’s last long spell out of office from 1951 to 1964, it was the Left which gained the ascendancy. Its political programme, the Alternative Economic Strategy (AES) will be discussed a little later, but almost all the Left, including groups as disparate as the Labour Co-ordinating Committee, Trotskyists groups and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD) sought to use democratic accountability as a means to ensure that never again would a Labour government ignore its members and affiliates while going cap in hand to international capital.

This was a consequence of the failure of the Callaghan government to implement the radical ideas of the 1973 manifesto. The introduction of the re-selection of every Labour MP during the life of a parliament in 1979 provoked a revolt by many on the Labour right. This intensified when in 1981 an electoral college replaced the parliamentary party as the mechanism for electing the Labour leader. Under the leadership of the Gang of Four, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) was formed. However, supporters of the breakaway stayed long enough in the Party to defeat Benn’s challenge for the deputy leadership. Denis Healey won by a tiny margin, 50.43% to Benn’s 49.57%.

Tony Benn was often criticised by the left for approaching his socialism from above. A future left-lead Labour government would legislate socialism into being. On this reading, Bennism was a project disconnected from the wider trade union movement and community activism.

In fact, Tony Benn understood well the desperate need to link the Labour Party to wider civil society struggle. The Chesterfield Conferences held throughout the 1990s attempted, with mixed results, to link the Labour Party left with extra parliamentary campaigns.

In the 1983 election Labour won only 209 seats and 27.6% of the vote. The Tories’ overwhelming victory – they won 309 seats – is explained in large part by the size of the SDP/Liberal Alliance vote. They took 26% of the vote, almost exactly splitting the opposition to the Tories. The Party’s manifesto, dubbed the ‘longest suicide note in history’ by Gerald Kaufman MP, is simplistically cited by the Labour right then and now as the key driver of the Party’s electoral collapse. But as Michael Foot himself has pointed out in an interview with BBC On-line:

‘It has long been said that our main problem in 1983 was our manifesto – but the manifesto did not really play a part in the General Election – our defeat was also partly down to the atmosphere of the Falklands War.

‘…at the same time, part of Labour’s trouble came with the emergence of the SDP in 1981 which took away a great chunk of our support – this proved to be the absolute number one reason why our vote fell so low…’

Foot was right to identify the role of the defectors in handing Thatcher the keys to No.10. But his belief in a Party ‘represented by both its left and right wings’ was misplaced. Electoralism and hostility to socialism permeate the Labour right to such an extent that Party democracy is often seen as an obstruction to their assumed place at the centre of British politics.

In 2019, when seven right-wing Labour MPs – this time in alliance with a small number of Tory parliamentarians - once again sought to derail the left as a critical General Election loomed. The performative departures of media-compliant actors such as Chukka Umunna was only one part of an orchestrated campaign of sabotage. Change UK may have narrowly missed the ignominy of recruiting Ian Murray MP to its ranks. But it’s efforts were effective in compounding a carefully managed perception of a Party haemorrhaging its brightest and best.

As Nye Bevan had pointed out years before, ‘The right-wing of the Labour Party would rather see it fall into perpetual decline than abide by its democratic decisions.’ In response to Corbyn’s crushing victory in the 2015 leadership election, Tony Blair confirmed Bevan’s fears; ‘I wouldn’t want to win on an old-fashioned leftist platform. Even if I thought it was the route to victory, I wouldn’t take it.’

In 1983 Neil Kinnock was elected leader and Roy Hattersley deputy leader – the so-called ‘dream ticket.’ They subscribed to the official view that Labour had lost the two previous elections because it wasn’t perceived as sufficiently centrist. Hence the new leadership began the task of re-asserting Labour as a Party of moderate reform, with the emphasis on moderate. Any Left influence would be reduced by attacking democratic participation from below.

This was not a simple task. In 1984 the miners’ strike offered a catalyst for wider class struggle. Kinnock distanced himself from the dispute. He criticised Scargill for his conduct of the campaign, accusing him of acting like a First World War general. But he remained indifferent to police and state abuses in undermining the strike.

The attempt to accommodate Labour to the centre ground was to no avail. In the 1987 election, despite an improved electoral performance – the Party gained a 30.8% vote share - the Tories still won. In a typical act of right-wing arrogance, ex-Leader James Callaghan had used the election campaign as an opportunity to attack the Party’s policy of ditching Trident.

Determined to learn all the wrong lessons, the Party leadership responded to the defeat with a review of policy, Meet the Challenge, Make the Change. Designed to distance the Party even further from its founding convictions, it arrived at Conference alongside all other policy documents. Despite its significance, the Party was not allowed to table amendments. The broadsheets sung its praises as clear evidence of Labour acknowledging – finally! – the primacy of capitalism.

The years to 1992 saw increasing signs of a retreat by the Labour Party left. In 1988, Benn mounted and lost a leadership challenge to Kinnock by 88.63% to 11.37%. The left had been spilt over the wisdom of Benn’s challenge, with many fearing the campaign would expose the weakness of the left’s position.

This weakness was evident during the anti-Poll Tax campaign. The Party leadership could not be pressured to sanction a national demonstration despite universal hostility to the tax. Kinnock’s office craved total electoral respectability, and playing to the right-wing gallery, the London demonstrations were dismissed as the work of ‘toytown revolutionaries.’

And yet despite all attempts to demonstrate that Labour was as timid as its 1929 iteration, in 1992 the Party lost again, with the Tories being returned on a reduced majority of 21. John Smith succeeded Kinnock, but was to die only two years later. Tony Blair won the subsequent contest with 57% of the vote, the first to be contended on a one member, one vote principle.

The End of (that) History

The Labour Party Left has never enjoyed a golden age as far as Left policies, or an active and assertive membership base with close links to extra parliamentary movements is concerned. This objective truth rather undermines the position of those who argue for leaving the Party when things are difficult, or the Left has only limited or declining influence. This has always been the case.

In the 1970s and 80s, the Left won considerable support among rank-and-file activists, coming close to winning the leadership of the Party. Why did it fail? It faced formidable opposition, both inside and outside the party. However, the Left which fought the battle for democratic reform, spearheaded By Tony Benn and the likes of the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy, failed to develop a political strategy that could secure effective purchase amongst members, the trade unions and crucially, in working class communities. As the eighties wore on, the political strategy that had been developed became increasingly irrelevant. Benn attempted to re-energise efforts towards forging alliances between the Labour Left and wider civil society, most notably in the form of the Chesterfield conferences. But when the right launched their counter attack through Kinnock, then Smith and finally Blair, there were no forces inside the party sustained by communities of resistance outside which could defend socialist strategies and organisation.

What Happened?

The demographic changes of the decades since have been profound. As de-industrialisation continued apace, class composition was irreversibly transformed. Trade union density and workplace power declined proportionately. Collectively, the left has failed to grapple with the restructuring of capital which has impacted in a number of interrelated ways.

The left’s response largely remained within the confines of its established repertoire of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary actions – the raising of issues within the UK and devolved parliaments, strikes, sit-ins, boycotts and demonstrations which attracted fewer and fewer people. There was a failure to push beyond accepted boundaries of left thinking. No new vision emerged, no new forms of struggle, no strategy which resonated with the lived experiences of working people or those whose concerns with the environment, gender, sexuality or race led them to question the nature of their society.

This was in stark contrast to the situation after the Tories took control in 1979. Determined to carry out a long overdue restructuring of capitalism the Tories intervened to create conditions where the traditional responses of the labour movement were tested to destruction, and found wanting. Thatcher’s mantra of ‘management’s right to manage,’ while by no means uncontested, led to an ever-decreasing share of national income for the many. Inequalities rose dramatically between 1979 to 1991. The results of this strategy were catastrophic. The first two terms of Tory rule saw a loss in manufacturing jobs greater than in the thirteen years of deindustrialisation which preceded it.

After half a century of deregulation, privatisation and a retreat from redistributive ambitions across the political spectrum, the OECD places the UK as the 9th most unequal country amongst OECD nations. According to the Equality Trust, the top 5th take 36% of the country’s income and 63% of its wealth. Meanwhile, the bottom 5th have 8% of total income and 0.5% of wealth (The Scale of Economic Inequality in the UK - Equality Trust). According to Oxfam, the global picture makes for dystopian reading. The world’s 2,153 billionaires have more wealth than the 4.6 billion people who make up 60% of the world’s population (World’s billionaires have more wealth than 4.6 billion people | Oxfam International).

Left economist Andrew Fisher describes this period as the ‘failed experiment,’ where the hegemony of the marketplace became almost unremarked on, insulated behind an ideological consensus where redistribution became a byword for the politics of a time long gone. As Thomas Frank, quoting Luttwak, describes it in One Market Under God (2000):

‘At present, almost all elite Americans, with corporate chiefs and fashionable economists in the lead are utterly convinced that they have discovered the winning formula for economic success, the only formula – good for every country, rich or poor, good for elite Americans:

PRIVATISATION + DEREGULATION + GLOBALISATION = PROSPERITY.’

New Labour Chancellor Gordon Brown had declared an end to ‘boom and bust.’ The end of history had arrived. We were, apparently, ‘all middle class now.’

New Labour had not only accepted globalisation, it had embraced it. A commitment to low taxation, low inflation, deregulation and low social costs confirmed its co-option into the neo-liberal order. Low taxation was the inevitable corollary of private enterprise culture, a form of meritocracy where rewards and risks would incentivise the entrepreneurial and punish the ‘lazy.’ An ‘extreme individualism’ took hold. There were to be no rights without responsibilities. As with any new ideological settlement, failure to comply with the demands of the new social order came with a freshly minted vocabulary of condemnation. The miners had been the ‘Enemy Within.’ Now, those not fortified with the go-getting spirit of the age would have to fall by the wayside, condemned as an ‘underclass,’ Charles Murray’s ‘social plague’ loitering on the fringes of an unforgiving meritocracy.

Education was to provide the ticket to limitless social mobility. If the government no longer had a leading role in creating employment through local or state ownership or intervention, it could instead ensure that workers had access to the skills necessary to make them attractive to putative employers. According to Robert Kuttner in his contribution to On the Edge (2000):

‘There is one true path to the efficient allocation of goods and services. It includes above all, the dismantling of barriers to free commerce and free flows of financial capital…to remove…distortions to the laissez faire pricing system; to dismantle what remains of government industry alliances.’

These were not immutable laws of economics, but political choices. But they were presented as fait accompli, forces of nature politicians had no option but to facilitate. In the Blair Revolution (2004), Mandelson and Liddle argued that:

‘The new international economy has greatly reduced the ability of any single government to use the traditional levers of economic policy to maintain high employment.’

Wendy Alexander, Scottish Labour leader from 2007 – 2008, stated in a Sunday Herald interview on 2002 that:

‘The role of government is to say that instead of providing a safety net – we can’t guarantee you a job for life – we can provide you with a trampoline that makes you feel confident and makes you feel secure enough to move between jobs. My entire skills strategy is about making that trampoline.’

Recording the glowing testimonials to the transformative impact of a deregulated world where the atomised but educated worker could ‘get on their bike’ and locate work during a free afternoon would fill these pages and many more. Neo-liberalism’s true believers were nothing if not an evangelical congregation. But only a short few years later, their faith in the new economy would be challenged by the most catastrophic crisis to destabilise global capitalism since the 1930s.

The Unlikely Return of the Labour Party Left

In 2015, in the words of Novara Media’s Ash Sarkar, Jeremy Corbyn, an unassuming Socialist Campaign Group backbencher, won the leadership almost ‘by accident.’

Of course, though history is littered with the vagaries of chance, Corbyn’s victory owed much to a series of specific historical, political and sociological events. Previously, the rise of Tony Blair to the leadership of the Labour Party appeared to have sounded the death knell for any notion of Labour being re-purposed as a vehicle for socialist politics. John Smith’s rejection of socialism in favour of social democracy did at least retain a kernel of reforming, redistributive intent. In contrast, Blair and his coterie of technocrats forged a Third Way committed to making peace with an apparently hegemonic neo liberal order. This pact-of-convenience was to unravel in spectacular form in the wake of the 2008 banking crisis, the collapse of the Labour government led by Gordon Brown, and the advent of austerity as shock doctrine.

The invasion of Iraq, and Blair’s dismissal of mass demonstrations against the prospect of an illegal war, had already exposed the first Labour PM since 1979 as an expedient politician every bit as mendacious as the predecessors he claimed to depart from. The 1997 Labour government had secured a landslide victory, and set about its first term with some zeal. Constitutional change, the Good Friday Agreement, Sure Start centres and a minimum wage came quickly, only for the energy of that early promise to fizzle out. The pragmatism and ‘electability’ they claimed set them apart from a Left content to shout from the side-lines became an albatross around New Labour’s neck. Shorn of any desire to confront capital (in the form of the disastrous PFI, Blair’s Cabinets were in fact anxious to invite predatory capital into the heart of the UK’s public services), a caste of professional politicians soon ran out of courage and ideas. Peter Mandelson sought to ease the membership’s fears by claiming that Labour voters had ‘nowhere else to go.’ In 2010, the Prince of Darkness discovered that Labour voters had indeed found an alternative box for their X. Either that, or their growing disaffection with a Party so timorous it meekly accepted a Tory narrative which located the 2008 crisis as a consequence of government over-spending led them to spend election day May 6thth 2010 at home.

Despite its founding ambitions, the Blair project failed to reconfigure UK politics. The alliance with the Liberal Democrats never made it out the plotting stage. The Tories regrouped. A sclerotic, centralized British state remained unmoved by a devolution of powers to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Clause IV was abolished. But the UK public stubbornly refused to subscribe to the notion that the private ownership of the means of production was anything other than an establishment scam in plain sight. Blair had boasted of retaining the least liberal trade unions laws in Europe. But the movement remained resolutely affiliated to the Party he led. From 1997 onwards, Labour haemorrhaged public support, holding on to ever decreasing majorities thanks to the implosion of a Tory Party at war with itself, and the largesse of the First Past the Post electoral system.

A Socialist Response

When Tony Blair confessed, in 2016, to ‘be baffled…I’m not sure I understand politics right now,’ his bewilderment wasn’t caused by a world plunging towards climate catastrophe while experiencing ever increasing income and wealth inequalities, circumstances which, as UK PM for over three terms, he could take some responsibility for failing to address. Nor was it the surrender of the Labour Front Bench to the narrative of perpetual austerity that confused the erstwhile landlord and head of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. What perplexed the ex-PM was Jeremy Corbyn’s landslide election victory in the 2015 leadership contest. Gordon Brown ominously warned members not to become ‘a party of protest’ (an admonition that was to be rolled out every time the party showed signs of declining to be a doormat to capital). Peter Mandelson told the Financial Times that ‘the Labour Party is in mortal danger.’ The cause of their hand-wringing? An increase in membership leading to an extra £9,532,000 in the Party’s coffers. Those numbers were to increase again during the infamous ‘chicken coup’ of 2016, when Owen Smith was identified as the hapless patsy capable of restoring order. The extraordinary lengths the establishment inside and outside the party went to in order to delegitimise the Leader of the Opposition, and his Cabinet Ministers (at least those not busy orchestrating live resignations for a corporate media fixated on the minutiae of party machinations) as political actors was unprecedented in British political life. Margaret Beckett, furiously back peddling to atone for the crime of nominating Corbyn in 2015, a sin Blair and Jim Murphy adviser John McTernan described as ‘moronic,’ joined other Labour grandees in bemoaning the imminent collapse of the UK’s social order should Corbyn become PM. As the BBC asked ‘Has Corbyn Ever Supported a War?’ military leaders publicly considered mutiny should a Corbyn led government ever be returned to office.

Mounting allegations took their place in a very long queue. Corbyn had, apparently, been a Czech spy during the Cold War. Even more scandalously, he was wont to wear a hat bearing a suspicious resemblance to one worn by Lenin almost a century previously. The ruling class and its media stenographers would not rest until they found mud that would stick. In the moral panic engineered around anti-Semitism, they were to find a means of beating Corbyn, and the party’s left, into the tightest of corners.

As Yannis Varoufakis has noted, the allegations levelled at Corbyn and his supporters from 2016 onwards could not be ignored. Lifelong anti-racists were being accused of secretly harbouring hatred towards the Jewish people. How could they not respond?

The history of those events has been well documented by both good and bad faith actors. Amongst the worst is producer John Ware’s Panorama programme Is Labour Anti-Semitic? Ware had set out to answer his own question in the affirmative, winning a BAFTA for his service to what, in ‘Manufacturing Consent,’ (1988), Noam Chomsky describes as the ‘media filter’ of ‘flak.’ To distract from the dangers of a growing or potential challenge to their corporate owners, the media will discredit and trash voices guilty of ‘straying from consensus.’ The party under Keir Starmer would subsequently apologise and settle with staff quoted in the programme to the tune of a six-figure sum. The WhatsApp comments from many of those involved betrayed misogyny, racism and a cynical desire to see Labour fail at the 2017 and 2019 General Elections. A similar amount of money was later squandered on pursuing, to no avail, those the post-2019 party hierarchy believed had leaked the WhatsApp files to the press.

Martin Forde KC would later confirm that anti-Semitism had been ‘weaponised’ by right wing staff, who also found a variety of novel ways to sabotage the Party’s electoral efforts, as well as blocking investigations in to reports of anti-Semitism to undermine the elected leadership. Al Jazeera documentary series The Labour Files (2022) would go on to meticulously undermine Ware’s narrative. No matter. As the authors of Bad News for Labour: Anti-Semitism, Labour and Public Belief (2019) scrupulously recorded, the damage had been done.

In fact, it was only when new General Secretary Jennie Formby replaced Ian McNicol in 2018, and when Karie Murphy became Corbyn’s Chief of Staff, that complaints began to be processed efficiently. Forde would go on confirm as much in his report. Lord Ian McNicol is currently under investigation by the Lords standards watchdog for allegedly using his office for personal profit.

Why Corbynism failed is perhaps in retrospect just as important as why he was elected in the first place. The former offers a cautionary tale of how the left must approach the fire next time. The latter offers hope that, as was the case in the months leading up to the 2015 leadership election, no matter how bleak the landscape, history can throw socialists a surprising and hopeful turn when we least expect it.

Scenes from an Unexpected Victory

It was primarily those members who joined following Ed Miliband’s unexpected 2010 leadership victory who would go on to vote in decisive numbers for Jeremy Corbyn five years later. Miliband broke from the rhetoric of neo liberal austerity. He declined the toadying to Rupert Murdock and the right-wing press habitual to the Blair and Brown camps. A door-crack of political space opened up. When Labour fell to its worst General Election defeat since 1987, Miliband’s departure seemed a precursor to the return of a Blairite faction still smarting from the defeat of David Miliband as their anointed successor to Blair/Brown. But beyond the blinkered confines of Westminster and its media echo chambers, something was stirring. When Jeremy Corbyn announced his candidacy in the 2015 leadership election, socialists prepared themselves for a campaign of position. A brief public platform for socialist ideas would allow the Party’s beleaguered left to regroup, build and propagandise. But history had something far more surprising in store.

It is not the remit of this pamphlet to revisit and relitigate the years 2015 – 2019. An array of literature, journalistic and legal investigations tell that story in meticulous detail. We are all now familiar with the arc of events leading from the first minutes of Corbyn’s victory over opponents still wedded to the illusion of deficit reduction in the name of the austerity. ‘Jez we Did!’ rang out across CLPs. Tens of thousands of new members re-energised local branches. The fragile shoots of a party membership in lockstep with extra parliamentary civil society could be discerned. Corbyn’s first act as leader was to speak at a Refugees are Welcome event in London. New members were soon derided as ‘cultists’ and ‘hobbyists,’ as if a belief in the capacity of politics to transform communities could only derive from a mass hallucination amongst the young and biddable. When crowds from Glastonbury to Leith spontaneously burst into renditions of ‘Oh, Jeremy Corbyn,’ they did so in a spirit of hope and expectation. As Jeremy would go on to say, ‘It isn’t me they fear, it’s you.’ The neo-liberal project assumed an end to the active participation of ordinary people in cultural, economic and political life. Beyond formal elections arranged by professional politicians and their corporate media bag-carriers, the atomised consumer was expected to dutifully comply with their allocated marketised functions. When mass crowds attended Corbyn rallies, rather than embrace a joyous outpouring of long-repressed agency, class elites expressed the same fear and loathing organised dissent has always provoked from Peterloo to Orgreave.

Every possible means of de-legitimising this dangerous movement was test-run for impact. Corbyn was a Cold War spy, a threat to your family, a subversive hell bent on undermining national security. This quiet, unassuming and conflict-averse back bencher would single-handedly destroy the Labour Party. But it was to be the allegations of anti-Semitism, levelled against Corbyn and by proxy all those who supported his leadership, that would go on to inflict the most serious reputational wounds. As recounted in Bad News for Labour (Greg Philo et al, 2019), the manufactured moral panic made deep inroads into public opinion. When asked, focus groups assumed a rate of reported incidents in the party many times their actual number. Corbyn’s office was ill-prepared. Without a redoubt of support in the media, and with a majority of the PLP in open revolt and only too happy to endorse the charges, the left fell upon itself in sharp disagreement over how to deal with the crisis.

Shami Chakrabarti’s 2016 inquiry confirmed that the Labour Party was ‘not overrun by anti-Semitism, Islamophobia or other forms of racism.’ A cross party Home Affairs Committee rejected the allegations the same year. ‘There exists no reliable, empirical evidence to support the notion that there is a higher prevalence of anti-Semitic attitudes within the Labour Party than any other political party.’

Meanwhile, as later documented in a Hope not Hate submission to a Conservative Party inquiry into racism within its own ranks (2021), and earlier established by a YouGov (2020) poll of members, Islamophobia was rife amongst a majority of Conservative activists and elected representatives. Theresa May had been the architect of the ‘hostile environment.’ Boris Johnson was wholly comfortable railing against Islam, mocking African children and casually attacking the LGBTQ communities. The media looked the other way. The ‘filters’ of ‘flak’ and the ‘common enemy’ used to manufacture consent did not allow for the inconvenient story of a Tory Party riddled with hate to muddy the narrative waters. In the favoured establishment account, the Tories were to be the accusers, not the accused.

The ruling class and its attendants inside Labour had located an effective means of delegitimization. As Morgan McSweeney (previously Liz Kendall’s campaign manager in the 2015 leadership contest) and Labour Together insiders would go on to describe to the journalists Patrick Maguire and Gabriel Pogrund for Get In: The Inside Story of Labour Under Starmer (2025), the primary danger they saw facing the Party between 2015 and 2019 wasn’t a Tory party shifting rapidly to the right or the rise of UKiP, and the increasing concentration of power and wealth at the top of society. Instead, the very real possibility of a Labour government committed to a redistributive programme and a repositioning of the UK’s international relations posed an existential threat to the defenders of the status quo. By any means necessary, such progressive, potentially transformative projects had to be stopped. Hope was a dangerous contagion.

Learning, not Drowning

There is no shortage of journalistic work exposing the machinations of a coalition of self-appointed ‘Labour grandees,’ the right-wing press, lobby groups and a liberal commentariat unsettled by the prospect of a new political dispensation they were not invited to. From Philo et al (2019) to the London School of Economics media report (2016), Al Jazeera’s the Labour Files (2022), the Forde Report (2022), and the ‘Oh Jeremy Corbyn’ documentary (2023), a paper trail of lies, exaggeration and sabotage is widely evidenced. Some of those instrumental in the operations to disrupt the General Election campaigns of 2017 and 2019 are now embedded in the Labour Cabinet. Peter Mandelson once boasted of using his wide network of establishment connections to ‘bring down’ the twice elected leader of the Opposition. In 2025, Mandelson was appointed British Ambassador to the US. The ‘Dark Prince,’ twice sacked from Cabinet for financial improprieties and never more relaxed than when in the company of the powerful, recently demanded that the Ukrainian people accept whatever ‘peace plan’ the Trump administration foisted on them.

Ultimately, however, it was to be the Brexit vote that undid the Corbyn leadership. Having gone to the electorate in 2017 with a promise to honour the referendum result while extracting maximum concessions on workers’ rights, environmental and consumer protections in negotiations with the EU, the Party eventually adopted a position as impossible to defend as it was to persuasively articulate. The party would support a second referendum. Corbyn, who had spoken at more Remain rallies than any other Cabinet Minister, would

remain neutral, adhering only to the final outcome. It wasn’t enough for liberal opinion. Corbyn had betrayed their most cherished experiment, a neo-liberal European Union still trading on the days of the ‘Social Europe.’

The lessons of this heady, intoxicating but ultimately failed experiment in left leadership are still being processed. They may be summarised, though not exhaustively, below:

Should the party have moved to system of mandatory re-selection of MPs?

Did the leadership respond decisively enough to charges of anti-Semitism, not only in quickly addressing the small numbers reported, but in confronting the lies of an establishment whose own institutionalised racism it barely attempted to conceal?

Why did the left fail to build a campaigning hegemonic bloc after Corbyn’s 2015 victory? How do we succeed next time?

How can we prepare ourselves for the intensity of establishment counter-attacks on a future left leadership?

Commitments to legislation that might have drawn in additional progressive layers – for example, PR – were not effectively pursued.

The 2019 campaign sought to build on the excellent GE result of 2017. But ‘one more push’ proved an optimistic approach, draining activists of energy and initiative. The left became defensive, not offensive in its political culture.

As the left became increasingly distracted by the fallout from Brexit, its case collapsed, the left coalition fractured and its nerve failed.

Of course, throughout this time, and though not as unhinged as PLP attacks on Corbyn, Richard Leonard’s 2017 leadership victory attracted a parallel response from the Scottish Labour Party right. Anas Sarwar could not accept defeat. At the time of writing, ex MSP and Shadow Minister Neil Findlay has announced his resignation from the party. In reference to the UK government’s planned cuts to disability benefits, Findlay wrote, ‘In solidarity’ to all those ‘who will be affected by these vindictive and brutal policies.’ For his ‘own sanity, dignity and self-respect, I can no longer remain a member of the Labour Party.’

As an MSP, time and again Neil was forced to call out the hostile briefing, lack of co-operation and back-biting directed at Richard from erstwhile Cabinet colleagues throughout his tenure. Ultimately, Sarwar was to oust Richard in a ‘coup backed by Keir Starmer’ (Scotland's papers: Richard Leonard 'ousted' and fish prices crash - BBC News). As the 2026 Scottish General Election looms, Survation polling places Sarwar’s Labour Party in second place behind the SNP and only marginally ahead of the far-right Reform party (Survation | Reform UK Records Highest Support Ever in a Scottish Poll | Survation). In March 2025, 36 Labour MPs, fronted by the Labour leader and Scottish Cabinet Secretary Ian Murray, backed a letter urging the government to press head with devastating cuts to disability benefits.n

The Starmer Counter-Revolution: The ‘Grown-Ups’ Take Revenge

When Keir Starmer stood for leadership in 2020, his pledges, solemnly intoned throughout the campaign, included a 5% wealth tax, public ownership of utilities, the abolition of Universal Credit, the placing of human rights at the heart of foreign policy and the defence of migrant rights. On being elected, the language of redistribution was erased from the Party’s vocabulary. In its place, an ugly anti-immigrant rhetoric sought to outflank Reform by endorsing its messaging. In the wake of the 2024 racist riots that engulfed communities in England and Northern Ireland, Starmer visited Georgia Meloni’s post-fascist government seeking advice on immigration policy. On March 2nd 2025, reports confirmed further talks between the governments, with the Party seeking to emulate Meloni’s immoral decanting of asylum seekers to third party countries months after Labour abolished the hated Rwanda scheme. Previous to this, official Labour memes appeared on social media filming people being forcibly deported. Under Starmer’s leadership, the Party is in danger of inadvertently summoning the dark forces of the far right.

Starmer promised an end to internecine factionalism. Instead, he has become a ‘passenger in his own government,’ a vassal for the factional ambitions of Labour Together and the Treasury orthodoxies driving his Chancellor’s fixation on deficit reduction.

The government is collapsing in the polls. It stands accused of complicity in Israeli genocide, an intensification of austerity, punching leftwards at those raising alternatives to the ‘failed experiment’ of deregulated capitalism, and downwards at those it implicitly accuses of being a brake on the god of growth. The UK’s social contract is breaking down. Increasing numbers are deserting their Party membership, reportedly at the rate of a member every 10 minutes. Overall membership dropped to 400,000 in March 2025, the lowest total since 2015. The far right is feeding from public disaffection in a system they know is rigged against them. Alienation and anomie disfigure communities. Poor mental health afflicts our youth, with many young men finding solace and identity in toxic social media landscapes.

Capitalist Realism or Socialist Renewal?

Rosa Luxembourg’s oft quoted warning of ‘Socialism or Barbarism’ has seldom been more apposite. Gramsci’s description of a dying social order playing host to ‘morbid symptoms’ in ‘a time of monsters’ seems precisely calibrated to describe the Nazi-saluting Elon Musk and the corporate and far right gangster-class of the Trump administration. In the post war period, sociologist CW Mills foresaw an entwined ‘power elite’ of economic, military and political actors committed to shared class interests at the expense of the American people. Now, Yannis Varoufakis and others warn darkly of a coming ‘techno-feudalism,’ a capitalist mutation shorn of economic and political plurality and indifferent to climate catastrophe and the fascist fires it is happy to toy with. In short, time is running out.

In Capitalist Realism (2009), Mark Fisher asked whether compound layers of capitalist ideology had snuffed out any hopes of progressive renewal. Popular culture was locked into a death-spiral of nostalgia and mediated spectacle. What Fisher would have made of those brief post 2015 days would have been instructive. The tragedy of his untimely death robbed our movement of an incisive cultural eye.

But the Left is not short on commentators willing and able to address the present malaise. Palestinian solidarity initiatives, climate activism and a growing awareness of the dangers posed by the post-fascism of Trump, Musk, Meloni and Le Pen provide grounds for hope that a renaissance of organised resistance is possible. Podcasts and left think tanks proliferate. The reputational losses incurred by a discredited political class provide an organised left with the opportunity to embed its story in the national conversation.

It is in the face of all this that we have to build our strategy for socialism. We have to accept the reality of a Labour Party that has never really espoused the socialist project, but has, since its inception, always been a ‘party with socialists in it.’ And this element, at times, had considerable influence.

We also have to recognise that the politics of the Labour left from the 70s to the early noughties became increasingly deficient. They did not connect with the wider community beyond the Party and they failed to take account of the increasing significance of the renewed globalisation of capital and how the left might deal with that.

The defeat of ‘actually existing Communism’ in the early 80s was seen as final proof of the inapplicability of socialist ideas. Martin Luther King’s ‘long moral arc’ had not bent ‘towards justice.’ Instead, the ‘end of history’ offered the immovable fact of capitalist hegemony. Decades of what has become known as ‘extreme individualism,’ and as Thomas Frank points out, a shameless ideological offensive not just to extol the virtues of the market, but to depict it as the guarantor of freedom and choice, have undermined democratic control, regulation and participation in public life.

There is a distorting effect caused by the Marxian analysis of the Labour Party. By arguing that Labour has, albeit with occasional reformist energies encouraged from below, accommodated itself to the capitalist system, we ignore the consequences had Labour not won office on numerous occasions since its birth.

There are two aspects to note at this stage. Firstly, the real reforms of the Labour Party, however much we feel these should have been transformative rather than reformist, would not have taken place. This is particularly the case in relation to social policy. It is worth reminding ourselves of some of those achievements.

In 1946 the National Health Service brought about free, compresence medical care. In the same year the National Insurance Act introduced compulsory insurance for most adults and benefits for the unemployment, sickness, maternity, widows and a death grant. When Labour was in office again in 1964 the Protection from Eviction Act stopped evictions of tenants without a court order. Industrial Training Boards were set up, obliging companies to contribute to a training levy. In 1965 NHS prescriptions charges were abolished (though reintroduced in 1968). In 1965 the death penalty was abolished. The Open University was given its Charter in 1969 to provide degrees. In 1970 local authorities were given the power to end the 11 plus and expand comprehensive education.

Of course, this list could be much larger. The New Labour reforms include the establishing of a Scottish parliament, Sure Start Centres, a minimum wage and the Good Friday Agreement. The period 1997 – 2010 also saw the Iraq war, increasing marketisation in the NHS, deregulation of finance and the retention, and use, of Thatcherite anti-union legislation.

But the record of Labour in government is especially noteworthy given the Tories, the capitalist class and the right-wing media were hostile to most of these reforms. Indeed, though it was a private member’s bill that brought in liberalising legislation for gay men in 1966 and the Abortion Act in 1967, it is fair to say that under the Tories such legislation might well have been blocked for many years.

Secondly, these reforms, in so far as they were radical, were radical partly because of pressure from the Left in the Party. As David Rubenstein points out in his pamphlet about the 1945 government, the Labour Left was highly critical of the Government’s programme.

‘One target of socialist critics was the government’s social policy, despite its efforts in this field. As early as 12th October 1945 Sydney Silverman sponsored a motion in the House of Commons calling, in defiance of Government policy, for an immediate increase in old age pensions. His motion attracted the signatures of nearly 170 Labour back-benchers. The next month a Labour rebellion in a Parliamentary Standing Committee resulted in a Government defeat over its attempt to delay the payment of benefit for industrial injury until the fourth day of injury.’

In other words, the socialist left’s role in the party, even in a more left-wing party, is to put socialism on the agenda. As Rubenstein puts it in relation to the Left of the 1945 Government:

‘…pride in the Government’s record and anxiety about its enemies by no means prevented the existence of an articulate left.’

It did not then, and it should not now. Especially when the politics of redistribution, or any sociological understanding of the impact of inequalities on the fabric of society, have been all but purged from the party’s official lexicon.

Early into its term of office, Starmer’s Labour government is already in crisis. Though reforms have been secured, not least on employment rights and rail nationalisation, but also on raising the minimum wage (though set at a level below the living income as defined by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation), Domestic Violence Protection Orders and climate targets, these qualified reforms do not add up to elements of a unifying vision of how the Party conceives of the ‘good society.’ Having deferred to the neo-liberal demand of small government ‘treading lightly’ on people’s lives, the Labour Cabinet has entered into a unilateral embrace of the hegemony of the marketplace. The left Rubenstein identifies as providing the leverage for much of its reformist past has seen its voice systematically removed from the decision-making processes of party and government. In this vacuum, timidity, and worse, a qualitative shift in what Reeves, Streeting and Starmer (and behind the Wizard of Oz curtains, Morgan McSweeney) believe Labour governments are actually for, has undermined the administration’s ability to steer a steady, and different, course.

The Labour Party is a terrain of class struggle, not simply one of a number of organisations we choose to intervene in, or not. The party has at times in its history most often reflected the interests of the ruling class and its domestic and imperialist ambitions. Starmer’s current trajectory may seem unprecedented. Certainly, Labour Together’ s hostility towards the left, and dissent of any kind, is of an order we have not seen for some time. But in principle, Starmer’s politics articulate a tradition that has existed in the party from its inception onwards. Namely, more or less complete acquiescence to the demands of capital.

But a parallel, dual tradition has always existed alongside it, one that identifies capitalism as the root systemic driver of inequality, poverty and our broader social ills. Winning the party, and the wider trade union movement, to that tradition is the key goal of Labour Party socialists.

Left-Wing Nationalism – an Incurable Disorder?

The SNP’s Growth Commission Report, published in 2018, set out its economic blueprint for an independent Scotland. Chaired by Andrew Wilson, a former MSP and Santander Director, the report was condemned in blunt terms by the pro-Indy left. Writing in Conter (2020), Jonathan Shafi described it as ‘…written as if the economic crises of 2008 and 2020 didn’t happen…(it) would lead to cuts and much else detrimental to…working class people across the country. Nicola Sturgeon is fully supportive of this prospectus, which should have been well and truly buried given the context of the pandemic and all that entails economically and socially.’

Despite being launched by a well-orchestrated media campaign, the report has since been quietly but definitively forgotten. Canny references to Denmark and Finland could not obscure Wilson’s embrace of ‘a pro-free market vision for Scotland.’ (Kerevan, 2020). The SNP’s carefully choreographed positioning as a radical alternative to the ‘Red Tories’ of the UK Labour Party meant that Wilson’s candid assessment of a likely period of post-independence austerity was a sellable quid pro quo for only the most biddable of nationalists. Wilson was only supposed to ‘blow the bloody doors off.’ Instead, the Growth Commission exposed a post independent Scotland tied to monetary policy dictated by the Bank of England. This was a strange form of sovereignty.

Undeterred, the SNP continue to position themselves, if only rhetorically, to the Scottish Labour Party’s left. The ‘incurable disorder’ of ‘left-wing nationalism’ (Left Wing Nationalism – an Incurable Disorder by Mike Cowley – Red Paper Collective) has never been an easy illusion to maintain. In government, the SNP has declined to fully utilise powers that the STUC’s Budget for Communities report (a-budget-for-communities-stuc-briefing-on-budget- november-2024.pdf) points out could raise an additional £3.7 billion a year for public services. In 2024, the Scottish government scrapped its commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 75% by 2030. Reforms such as the broadening of eligibility for free public transport have been widely welcomed. But since 2008, education and health inequalities have increased, the housing crisis remains unresolved and drug-related deaths continue to spiral.